How to Find Frontiers

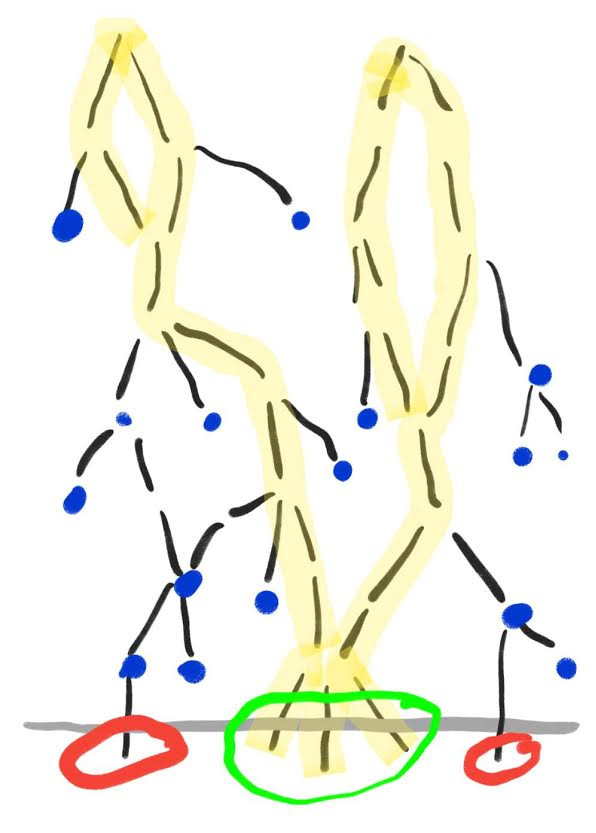

The history of anything looks sort of like this image.

Each black line is an idea or direction that depends on one or more earlier ones. The top is the beginning of the known history of the subject, and the gray line represents the present. The green circle is the mainstream thinking on the subject. The red circles are out-of-the-mainstream thoughts, but with current adherents.

The highlighted yellow sections are what we learn as “history” – the “just so” account of how the current set of mainstream ideas falls logically from every previous (yellow) idea. We probably know a little about the red circles, but we don’t learn much of the ancestors of the red circles, so they don’t make much sense to us. Why don’t they follow they follow the nice logical yellow path?

I want to learn about the blue dots. Not because the yellow brick road isn’t important to understand – it surely is. But simply by existing in society, we learn quite a bit about the yellow. Furthermore, since the yellow path is the path to mainstream views, most modern analyses of it are colored by the green circle. It’s difficult to tell what was truly thought at each step of the yellow because the precursors to the green bits stand out to us as obviously true and important, while that may not have been obvious at the time.

Blue dots are often forgotten, deprioritized, or sometimes even outright repressed. There are probably few if any adherents to modern descendants of their ideas. Thus, there are probably few modern analyses of them, and you’ll probably have to read a lot of original sources. But those sources will argue passionately about topics that you didn’t even know could be questioned.

Some worry that the blue dots are dangerous, or at least a waste of time. After all, if they were abandoned, surely that happened because they were inferior? And if they were not abandoned but actively destroyed by some group in the yellow path, then aren’t their ideas a threat to our green circle way of life?

To the first question, I would say that selection is fickle and often dominated by unexpected factors. For example, why were there so many memes that encouraged you to copy-and-paste themselves to re-share them? If you try to analyze memes in terms of how they benefit their creators, you wouldn’t have predicted that. The reason why they propogate is because that encouragement is good for the meme, which is orthogonal to the truth of the meme or the power or desires of the person who created it.

To the second question, while that may have been the case at the time when the splits happened, blue dots are very rarely dangerous. After all, by definition they have no or very few modern adherents. The red circles are the ones to be careful of, because they have communities, while the blue dots just have ideas obscured by time and distance. If you’re really worried, choose the blue dots that don’t even have any modern descenedents.

Thus, if you want to maximize the number of genuine new ideas learned, study the blue dots.

Here’s some exampes in several subjects.

The cultural history of the world follows this pattern quite clearly. The history of western civilization is the yellow path, but there have been many cultures that died out with no modern descendants – or, at least, no modern “mainstream” (= western, for me) descendants.

There’s one large red circle around most Islamic countries, where it’s difficult for westerners to understand what they believe and why, because we don’t know what their ancestor blue dots believed.

There are also red circles around isolated tribes, like those in Brazil and New Guinea. Their way of life looks incredibly foreign to us, because they descend from a very long line of blue dots. If you want to understand other paths that western civilization could have gone, study these blue dots. Debt: The First 5000 Years by David Graeber and Guns, Germs, and Steel by Jared Diamond are not bad places to start.

The linguistic version of this traces the influences very distinctly. If you want to learn about the nature of language, make sure to study dead and dying languages at least as much as you study Indo-European, Sinitic, and Arabic languages.

In politics, there are plenty of eloquent writings arguing for political opinions that are unthinkable now, but give you a much broader picture of the space of political theories. Want to read a 1680 argument for how the natural authority of fathers in a family means kings should have absolute authority? Try Robert Filmer’s Patriarcha. An argument against the US Declaration of Independence? Thomas Hutchinson’s “Strictures upon the Declaration of Independence” is quite readable. A more recent example that borders on red-circle ideas because the author is still alive is the Unabomber Manifesto. I agree with none of these works, but I’m glad to have read them.

In programming, the primordial ooze brought forth a few original principles. Some viewed programming as an extension of electrical engineering, while others viewed it as applied math. These ideas mixed early on, but some areas stayed relatively pure – there’s not much category theory in embedded programming, for example.

The mainstream of programming systems feels fairly broad – there’s dozens of mainstream languages and operating environments on eveything from embedded systems to enterprise development to academia. It’s easy to feel like everything we ever discovered or invented has been swept into the mainstream of programming thought.

Of course, we know that isn’t true. Whatever happened to Plan 9? That was the future, once upon a time, but it appears to have zero direct descendants. How about Prolog? Smalltalk? They’re blue dots.

Zooming user interfaces, a la Jef Raskin’s The Humane Interface, were thought by some to be the natural next step for interfaces. A very limited version exists in Prezi, but the only active project I know in the space that’s trying to make a true computer interface is Eagle Mode, which is a one-man project.

Lisp machines have famously been abandoned as hardware projects, though Lisp is still alive, and some Lisps may even be considered mainstream. If you’ve spent your life in x86, maybe take a peek at a Lisp machine.

Interactive storytelling is historically an off-shoot of mainstream game development, kicked off by Chris Crawford’s Dragon Speech, which is worth watching even if you’re not into game development. Interactive storytelling isn’t an ancestor of any mainstream ideas. The most direct impact has probably been to the modern interactive fiction hobbyist subculture – itself a backwater of computing, descended from Infocom text adventures.

I’ve learned some about these particular blue dots, but there must be so many more that I haven’t even heard of. That’s why I intentionally keep an eye out for these sorts of projects and try to learn about them whenever I can.

Every once in a while, you’ll follow one of them into the mainstream. I watched cryptocurrency go from an obscure backwater idea of cypherpunks to being regularly discussed in the Wall Street Journal. All of a sudden, the history and ideas of cypherpunks is not a blue dot – it’s been marked over with a yellow highlighter because its descendant has moved into the green circle.

People claim to be explorers and to love frontiers, but they complain they can’t find the “next frontier” until it’s already mainstream. In reality, they’re not interested in frontiers, they’re interested in getting in cheap on the ground floor of a new city. That certainly sounds exciting, but it’s not the same thing, and the skills and strategies are not the same.

If you’re looking for where the next big city will pop up, you should monitor the reports of all the explorers and watch for someone who has money to start building something – perhaps a railroad, a mine, or a large agricultural area.

A mountain man, on the other hand, should learn where people have gone before and follow their paths as far as they can, then wander off into the unknown. It’s not the most lucrative profession, but the views are unbeatable. You might discover a new lake, be the first to the south pole, or even find a fertile new land that settlers will one day colonize, based on your reports. If you don’t love the frontier for the frontier’s sake, this is probably not a great way of life. But you know that there are endless frontiers for those that look.

There’s a third type of person. They hears about explorations, maybe even go on a few. But they’re neither satisfied with simply experiencing the frontier nor predicting where the next boom town will be built. They’re looking for a place where they can start building something new. Maybe they’re looking for a place where they can start a mine, a ranch, or a new trade route like the northwest passage, the Panama Canal, or a mountain pass. Maybe they’re just looking for a place where they can worship according to their own creed.

All three people are valuable. I started programming as the second type, just climbing mountains because they were there. But as I crested a mountain pass deep in the wilderness, I came across the most fascinating little project I’d ever seen. Now, I don’t simply want to experience new worlds, I want to build one. I have a vision of the city we can build here, and I want to build that. For me, that manifests itself as working on Urbit, which is a software project that falls squarely in a red circle of programming.

All three types of frontiersman benefit from reading the reports of those that explored before them and maybe going to see these places in person, even the ones that looked like dead ends. Sometimes you just have to go a little farther.

If you’re a city-dweller, then as long as you’re not a cartographer, you’re probably fine focusing on the green circle and the yellow path, with a little of the red circles thrown in for flavor. But if you’re a frontiersman of any kind, study the blue dots!